IMPORTANT: WE HAVE MOVED!

CLICK HERE FOR OUR NEW SITE!

While the biggest event in Fashion x History has just concluded, judging from the turnout at the Met Gala, one can conclude that dressing to the theme isn’t quite a forte of A-listers. In the name of greater good, this series will demonstrate how one can be fashionably historically-inspired, while still adhering to certain themes.

AUSPICIOUS BIRDS AND US

Birds have had a long history of being seen as auspicious creatures and totems in Chinese culture. The Sun, for example, was represented by a three-legged bird. And of course, we are all very familiar with the phoenix, which at some point became synonymous with the bird in question I’m discussing today.

It has been known by many names in the Eastern part of the world, Zhu Que by the Chinese, Suzaku by the Japanese, Jujak by the Korean and Chu Tước by the Vietnamese. It symbolised the southern constellations of the night sky, and the element Fire.

Because of its association with fire, the vermillion bird is often thought to be the phoenixes by the West. And yes, plural because the Chinese Phoenixes fenghuang had gender (Feng was the male, and Huang was the female, and they combined into a singular identity somewhere down the road later on), while the Vermillion Bird did not.

The phoenix was believed to have the colours of the rainbow while the Vermillion Bird took its colour from the fire. Was that a phoenix or a vermillion bird that we spotted in Mulan? hmmm…..

Although some sources said that the ancient Chinese thought the stars in the southern night sky resembled the vermillion bird, thus the assignment of this symbol, it is unlikely so as the Vermillion Bird of the South as well as the Black Warrior of the North did not come into existence in the constellation assignment until much later (about 2,000 years ago) while the ancient Chinese were already very familiar with the constellations for far longer and had assigned the Dragon and Tiger to them first.

THE STYLING

Since Tang and Qing dynasty has the most fun and daring make-up trends ands styles, our styles were mainly based on these two periods, jazzed it up for modern taste.

This styling was designed in collaboration with Aaron Han (@aharw) assisted by gabby @ga.bae.be

Makeup assisted by Danny @chenlingx0 and Silas @operatang

Photo by Aaron and I

The styling was done in a manner to represent the animals but also not in a literal sense. The traits that are used are symbolic, just like the animal themselves are symbolic.

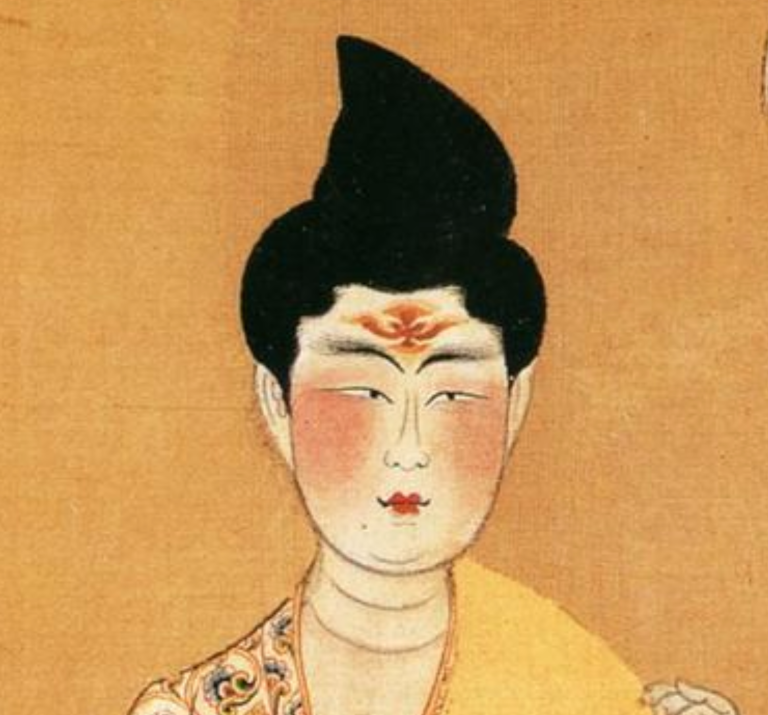

The Vermillion Bird obscures half of its face with a Bian Mian fan which is a half-oval type of fan with a history of over 2,000 years. Originally made of bamboo, it evolved to other materials overtime and the one in the shoot was made with an emerald green silk gauze with weaved patterns. Very understated, and quintessentially Chinese. Its subtletly is juxtaposed with the red feather nose piece of The House of Malakai styled by Aaron (@aharw) to suggest its avian nature. Of course, the collar design and the Tang style (circa 8th century) wing-like eyebrows are also suggestive of that.

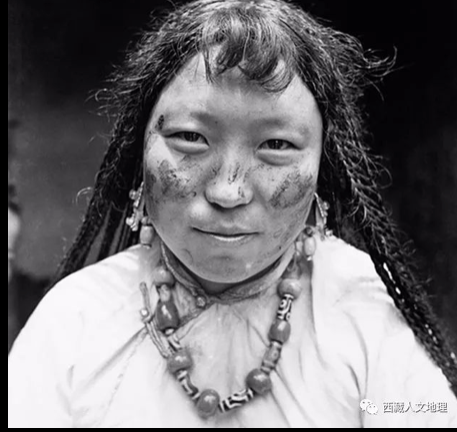

Underneath the nose piece, were rouge blushers across the cheeks which some might recall seeing on famous 90s Chinese singer Faye Wong, or more recently, singer Rainie Yang. Except that it’s a lot more intense, as it would’ve been how the Tang people of the 10th century were copying the Tibetans during that time in this style of make-up.

Obviously celebrities typically don’t do much research when they try on different make-up styles, pretty sure the socialites of Tang didn’t either, it was probably just cool or fun for them to experiment with a different styles because this style of blusher was deemed barbaric by the early Tang rulers, and had requested for the Tibetans to stop this practice. Who’d knew that a few hundred years later, it would become vogue at the end of Tang!

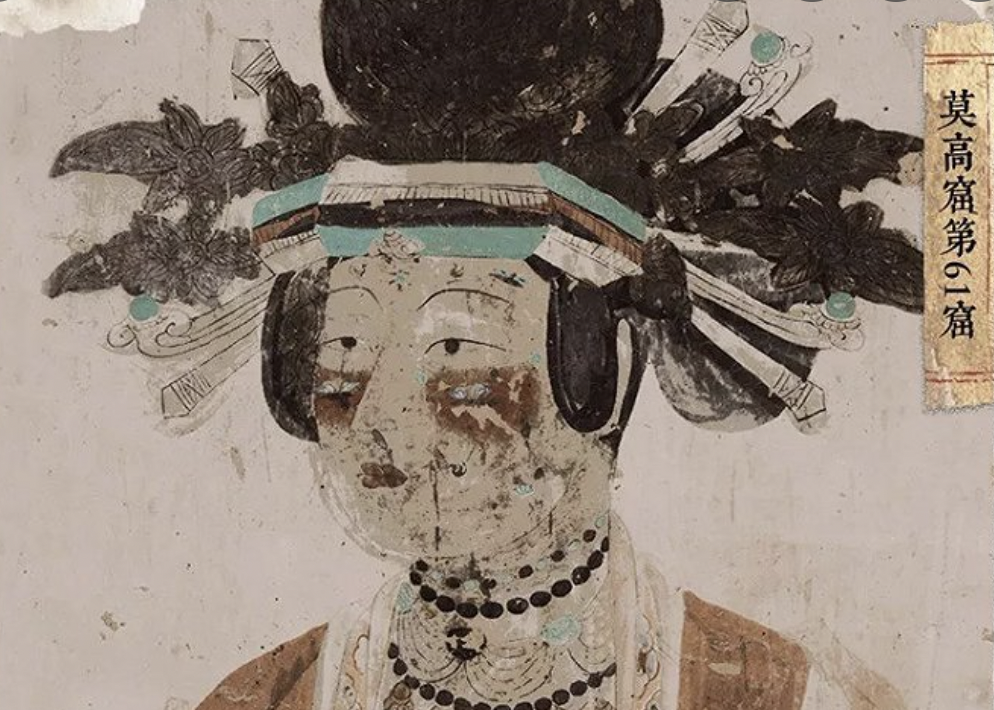

And just in case you thought the hair looks non-Chinese (like the typical long hair at the back in Chinese period dramas), I’d like to point you towards the Dunhuang murals from the Tang dynasty (same period), and look at the blushers and the hairstyle and accessories, it’s really quite Over The Top:

The lip was also historically based on the last dynasty of China—Qing dynasty. Similar to the Tang rulers, the Qing were not of the Han ethnic group although they have adopted a great deal of the Han practices after ruling over this Han-majority land for centuries. The Qing lip would typically be just a red dot on the bottom lip, but there were instances where the top lip was also painted fully.

The Modern Vermillion Bird wears vintage Thierry Mugler jacket, with big exaggerated shoulders but sleek silhouette to emphasize it being an animal of the skies.

The fringe skirt by Raf Simon for Calvin Klein is a reference to its long tail feathers.

Unlike the Phoenix, the Red Bird is just red, while phoenixes were said to be of rainbow colours.

The broad shoulder look was never really a Chinese thing, as sloping shoulder would look better in the traditional Chinese garment that has no shoulder seams. But that changed in the 40s with women adding shoulder-pads to their Cheongsams to accentuate the shoulder. This look is exemplified by the Japanese Singer in China Yoshiko Yamaguchi, most famously known by her Chinese stage name Li Xiang Lan 李香兰:

Right: Yshiko Yamaguchi/Li Xiang Lan in broad shoulder Cheongsam

QUINTESSENTIALLY CHINESE CRAFT, ACCESSORIES AND AESTHETICS

The Western fashion is very big on silhouettes of the dress, while the Chinese has always been about the hair, the craftsmanship, and the understated luxury where one needs to be close enough and in the ‘right circle of knowledge’ to appreciate the weave, the texture, the material, the motif etc. There’s a lot of secrecy behind many of the crafts, and that made them exclusive, therefore a sign of prestige for those who recognise them. Yet, in Chinese culture (quite unlike the Japanese), the craftsmen are anonymous, and undervalued in the grander scheme of things because the Chinese aesthetics has always been literati-led and the craftsmen were more of the ‘technicians’ to the literati’s ‘artistic vision’. Not unlike the many craftsmen working anonymously behind designer brands that bore the mark of the big name designers who most likely did not make those items themselves.

Bodysuit by Richard Quinn, Nose piece by Ricardo Tisci for Givenchy, styled by Aaron han (@aharw)

Hair and accessories by me, make-up by Silas and I.

And just to transition into the more purely Chinese look, we did another look with more Chinese accessories, and also a Tang style hair and make-up with Qing lips. You probably think that it is a copycat of Frida Kahlo, honestly we didn’t realise it until it’s been done, and I immediately recalled a stranger getting in touch to borrow from me my silk flowers for her dressed-up costume party (she stopped responding the moment I told her the price of the flowers. I know, the value of these things aren’t very apparent to those who are not familiar with them).

I use a lot of lacquer and silk flowers because they are so, so, archetypically Chinese but most people just think of Chinese = gold. When in actuality, Chinese didn’t really use much gold in the ancient past. Or Green Jade (Jadeite) for that matter.

Notice the green bangle? That is a vintage carved lacquer bangle (very rare to come by as typically it would be in red/cinnabar). Carved lacquer came about sometime during the Tang dynasty as well (circa 8th century or so) and became quite a thing later on so even though lacquer was used in many Asian cultures, carve lacquer can be said to be quintessentially Chinese. It is an extremely tedious process, as you would require hundreds of layers of paint, painted and dried, and painted and dried, before you can reach just a few centimetres of thickness for carving.

The Met (HAH!) had an exhibition on lacquer/cinnabar in 2009, you can read the synopsis HERE.

For the Traditional Chinese Vermillion Bird, I’ve decided to go with a wedding look because we often think of phoenixes for Chinese weddings, yet the colour that brides often wear for that occasion would be Red which is actually the colour of the Vermilion Bird. And since the Vermillion bird is often confused with the Phoenix, and more often than not used interchangeably with it, might as well throw the two into the same mix. If you can’t beat them, join them!

And you don’t say, Silas certainly looks a bit like Gemma Chan here don’t you think?

For this time round, she’s wearing cinnabar carved lacquer bangles. One is red-on-red, one is red-on-black. Both are vintage pieces.

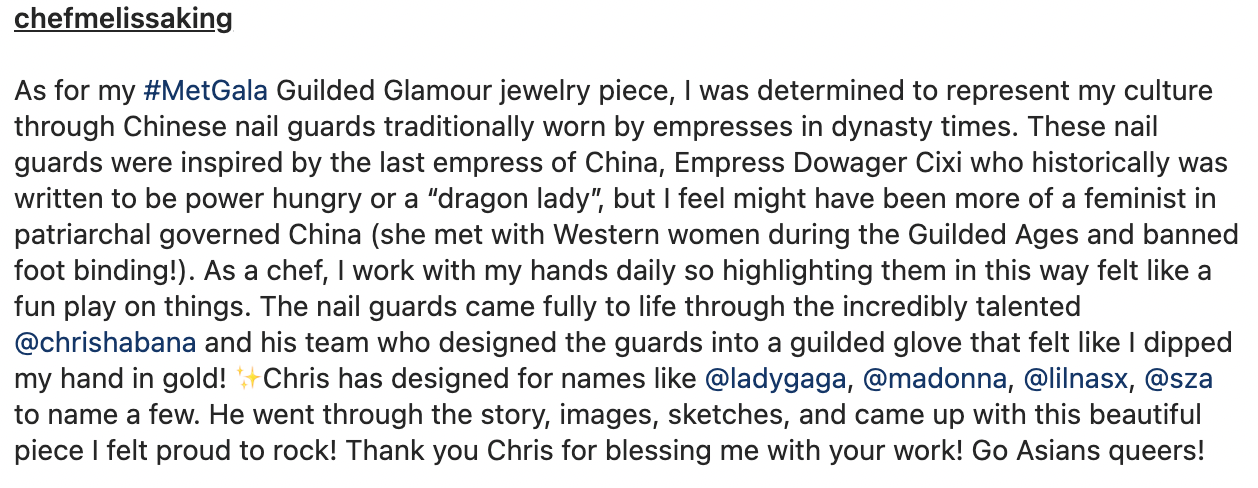

Now, I shall introduce you to the real Chinese filigree and cloisonné craft for hair accessories. Not the fashion jewelry type worn on the red carpet at the Met by Chef Melissa King for her nail protector. Apparently it was supposed to be inspired by Empress Dowager Cixi (who is, by the way, NOT the last empress of China, contrary to what the Chef wrote on her insta).

The thing about traditional craftsmanship that came from a lineage of thousands of years, is that they get finer and finer, and they are often consumed by the imperial family so the demand for finesse is extremely high. Also, they are all about understated luxury. If it’s that big a bling, it’s probably too crass for them.

The Palace Museum collection has quite a number of nail guards made from the Imperial Chinese filigree craft, completed with gems, pearls and kingfisher feathers on many occasions. You can zoom in to see the fine details of these nailguards, and they are extremely intricate —as fine as the kingfisher feathers.

In order to give you a bit more context on the scale of these intricacies, I shall zoom in a little bit on the filigree and cloisonné of the phoenix hairpiece in my photo which has similar craftsmanship as the palace museum nail guard above.

It is made with tiny grains of freshwater pearls and ruby (I think, I can’t remember the stones cos I have too many of these accessories.. lol). Her earrings are also filigree and cloisonné phoenix. SUPER AUSPICIOUS I KNOW!

I did an apprenticeship a couple of years back on filigree, cloisonné and kingfisher feather craft in Beijing, and it was through this process that I came to fully appreciate just how intricate this craft is. It’s not the type that you can see on photos or videos, that’s why celebrities wouldn’t really wear them because they don’t show up on screen that well cos they’re too tiny.

If you zoom in close enough, you can see that the edges of the wings is made up of tiny dots of gold. It’s actually very very fine silver threads gilded in gold, twisted into like a braid-like structure and welded onto the base. When I did my apprenticeship, the first thing to do was to learn how to pull the thick silver threads into fine strands, finger than human hair. And how to twist them in shape without breaking them. Sorry about the resolution, it’s just too fine for my camera. I will do better next time.

Since this set is all about intangible cultural heritage and fine Chinese crafts, I threw in the Kesi (literally translated to carved silk) fan. This is a replica of the Qing dynasty fan in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

The side profile you can see butterfly hair pieces made of dyed silk using the wound silk flowers craft, and also dyed goose feather accessories to replace the kingfisher craft. This hairpiece is based on the Qing dynasty item in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

The topic on Kingfisher feather is contentious, and there are many modern attempts to replicate the effect of kingfisher feather without the cruelty of it. Even the Qing dynasty rulers implemented a ban on using kingfisher feathers for accessories (with limited success obviously).

The cloisonné was one of the historical ways during the Qing period which middle class women could get a pseudo kingfisher feather colour accessory while the aristocrats continued with theirs.

These days, wound silk accessories, dyed goose feather, or peacock feathers are all reasonable substitutes. If you’re wondering (as I did), goose and peacock shed feathers quite readily and their feathers are abundant so it’s not like the case of the kingfisher where you need to kill many to get a tiny bit (disclaimer: goose and peacocks are not harmed since you just gather their shed feathers).

I’m actually making a series of accessories with these type of feathers and vintage lacquer pieces, and will be sharing them later half of the year! So stay tuned!

Meanwhile, if you’re planning to have a Chinese wedding shoot, please don’t go red + gold. It’s so cliché and nouveau riche. At least try to add some finesse like turquoise, blue, green, cyan, pearl, aquamarine, lapis lazuli, lacquer… They are going to add a lot more texture and colours to your otherwise crass look. We do, after all, have at least 5000 years of material culture and history to tap on, don’t behave like we only have 50.

Oh no, I was totally not referring to the billionaire daughter’s wedding (which one? so many huh.. :P).

POP CULTURE REFERENCE

The four guardians were first brought to my attention when I was a young latchkey child watching Japanese anime on my couch after school with my sister. Fushigi Yuugi was the name of the anime, and it started with the chapter of the Vermillion Bird of the South—Suzaku (in Japanese). It had all the characters with special abilities, each representing one of the 7 constellations of the southern nightsky under the charge of the Vermilion Bird.

So it is fitting that we start off this series with the Vermillion Bird.

DRAG IN CHINESE CONTEXT & AFTERTHOUGHTS

In the anime, the king of the southern kingdom Hotohori was a man who was as beautiful as a woman, probably very ahead of its time in the 90s.

And in this series, I have worked with Silas (@operatang) to portray this beautiful feminine side of a man. Drag is not new to Chinese traditional culture, except that it was not politicised like the West. The archetypical Chinese Opera look was a result of men trying to hide their masculine facial features in order to look more feminine. And beautiful men were a thing and even recorded in historical texts for thousands of years.

When I approached Silas for this project, I also intended to try to re-interpret drag as we know it today in a traditional Chinese manner—from the perspective of someone who wants to look as much like a woman in representation according to a male perspective. This is historically related to the oppression of women in public for about 500 years where images and representation of women were manifested through male bodies in public performances, through their ideas of what a woman is like, how we walk, how we talk, or by male painters.

So as a result, as it is today, men could be more ‘feminine’ than we are (small sample size, but the 2 women involved this shoot can attest to that!). Maybe femininity has often been depicted through the male gaze, so what we see is often a man’s ideal woman image (not how we actually behave, but how they fantasize us to be). So a man could possibly represent very well this ‘ideal femininity’ if they are in touch with their feminine side. Silas showed me some Asian drag queens who are absolutely gorgeous and live up to the ideal female archetype upheld by society (we’re all fellow subjects of the male gaze in this instance!).

I also wondered about the concept of ‘womanface‘ in western drag practices, where features of what it meant to be a woman were used as content for jokes, as part of the overall ‘ridiculous’ look. I’m not sure if I prefer that, or the over-romanticisation of female body during our oppression (as in the Chinese context). Two extremes of the male take on femininity.

Food for thought I guess!

AND because you lasted till the end of this article, you are rewarded with a Vermillion Bird Instagram/facebook selfie make-up filter! Click on the hyperlinked text to claim them:

INSTAGRAM

Vermillion Bird (without frame)

Vermillion Bird (with 5 choices of Chinese motif frames)

Vermillion Bird (without frame)

Vermillion Bird (with 5 choices of Chinese motif frames)