IMPORTANT: WE HAVE MOVED!

CLICK HERE FOR OUR NEW SITE!

My Teashake brings all the Boys to the yard,

And they’re like, it’s better than yours

Damn right, it’s better than yours

I can teach you, but I’ll have to charge.

-Some Song dynasty (10th-13th century) literati/ courtesan who adapted Kelis’ Milkshake lyrics

You know, this is actually a believable line in ancient Song dynasty (10th to 13th century) when it comes to tea, shaken (not stirred). And there is a 50-50 chance of it being sung by a Song courtesan, or narrated by a Song literati.

You’re probably thinking, why would anyone want to shake a cuppa tea? And why would it be sung or talked about by a Courtesan or Literati? Isn’t it just, tea?

So I would have to bring you to about a thousand years ago.. and introduce you to the wonderful world of Tea Battles where one’s brilliance is not measured by how big your muscles were, but swiftly they can help you move. In particular, your wrist. I will talk about that more soon.

THE TEASHAKE THAT BRINGS ALL THE BOYS TO THE YARD

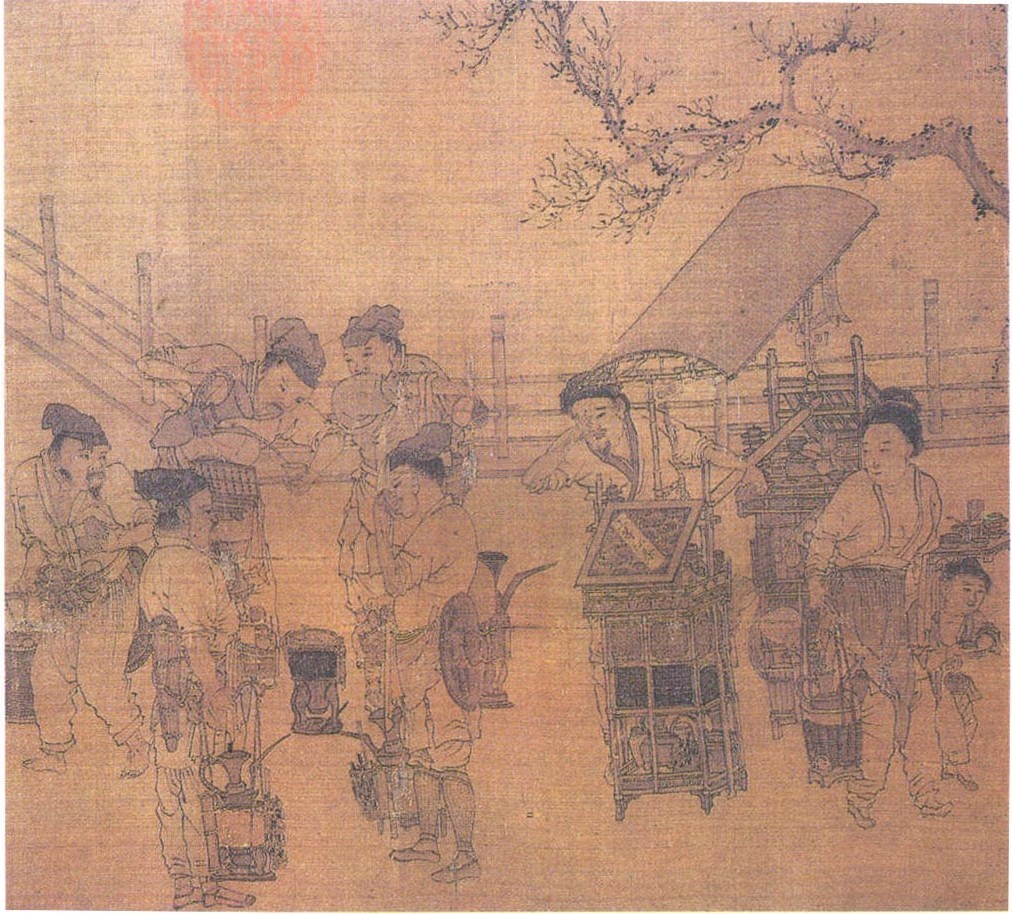

But first, here’s the entire process of tea preparation from breaking it down to smaller tea leave bits, to whisking it (that’s where the wrist part comes in, and is also one of the highlights):

You see, people of that period were drinking powdered tea, pretty much like the Japanese matcha that you are familiar with. The Japanese matcha was a continuation of that Chinese tradition, in fact, while the Chinese have long lost it although efforts have been made in recent decades to revive it with reasonable success.

An iconic Intangible Cultural Heritage tea practitioner of China who has been reviving this art for over 40 years said they looked to Japanese whisked tea practice and cross referenced with historical Chinese texts to understand and deduce how it might have been done in the past. How the Japanese have retained so much of ancient/medieval Chinese cultural practices is fascinating, and almost like how Chinese diasporas so faithfully tried to preserve their heritage after they have left China. Of course that being said, the Japanese definitely injected their own life and philosophies into whatever they brought over from China, and it became part of their very own, unique identity.

A good cup of tea, to the Chinese of Song dynasty, would be leaves from Fujian Jian’an region, plucked in the earliest part of Spring sometime in March (today, we generally thought of tea leaves from the middle of Spring in April as the best). Of course, there were specificities by the Song Imperial family on how exactly the tea leaf should look like—an eagle’s claw (lol, good luck figuring that out!)—and with a tiny bit of pale green (not green yet).

And this is the part where the tea gets shaken…really badly until it froths up like that hard peak when you beat your egg white for baking really fluffy cakes. Except that you use machine, and the Song people used their bare hands and a bamboo brush, sometimes with just a silver spoon (this is torture I tell you…).

And this is also the part where the flexibility and tenacity of your wrist muscle comes in…

If you can whisk some bubbles up, you have failed.

If you can whisk some foam up, you have barely passed.

If you can whisk thick foam up but it has some large bubbles, you probably can get a C grade.

If you can whisk thick foam with extremely smooth texture (like no visible bubbles), you can probably get a B grade.

If you can whisk thick foam that’s like the texture of wax and can last like 20 minutes without dissipating into the bowl of tea and can retain its thickness and texture when poured out well enough that you can even paint stuff on it with water or powder (phew that’s a super long sentence), then you can get an A.

But wait, as Asians, an A is hardly enough. You need Full Marks. So that means you need to ensure that your water temperature is right, and that in the entire process, you add 7 times water (no more, no less, you can’t shortcut this) with a specific type of water pitcher into a specific type of black glazed Chinese ceramic teabowl (click on link to see the Met Museum collection). This is observed and theorised in a book by the Song emperor Hui Zong, one of the most artistically acclaimed emperors in Chinese history with an exquisite taste and eye for great details.

THE DIFFERENT BOYS WHO ARE BROUGHT TO THE YARD

The middle class commoners

Song Dynasty was a period of great commercialisation and capitalism and the general middle class population were relatively more educated with a great appreciation for the finer quality of life. They were generally quite wealthy, and definitely enjoyed good shopping and parties. They started the first Night Market in Chinese history which operated till about 1am, and they take a break for 2 hours and reopens at around 3am. Even our nightclubs today doesn’t have that kind of vitality! So yes, the boys (and girls) were often out in their yard partying and getting high on tea (amongst other things, like booze but that’s a different topic for a different day).

Based on paintings from that period, it was also a period that greatly celebrated the middle class commoners and their lifestyles. Whereas periods before were much more of aristocratic-focused society.

The Literati, the Emperor and all his men

Song emperor Hui Zong was one of the most highly acclaimed artist-emperor of all times. He was a tea aficionado and as mentioned earlier, wrote his own theory about tea with great detail in a book called Treatise on Tea.

During the Song dynasty, literati and poets were often at the core of its political realm, philosophising and discussing state politics with the emperor thus further blurring the lines between arts and politics.

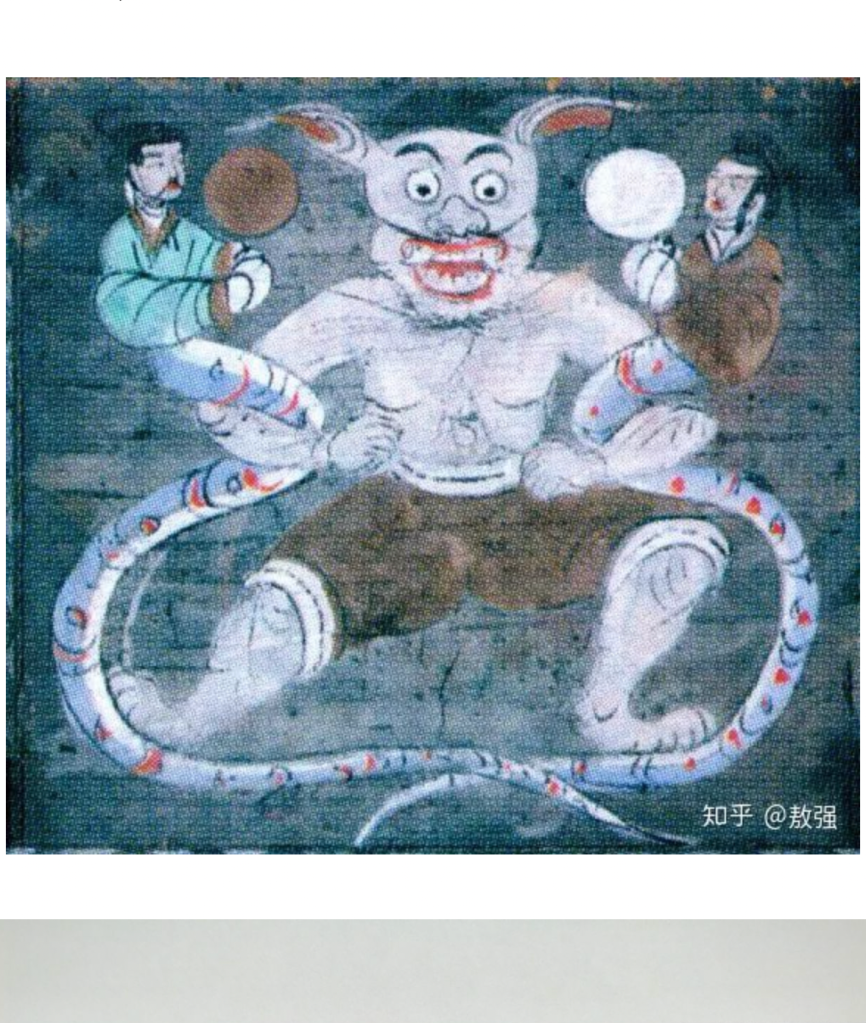

Monks

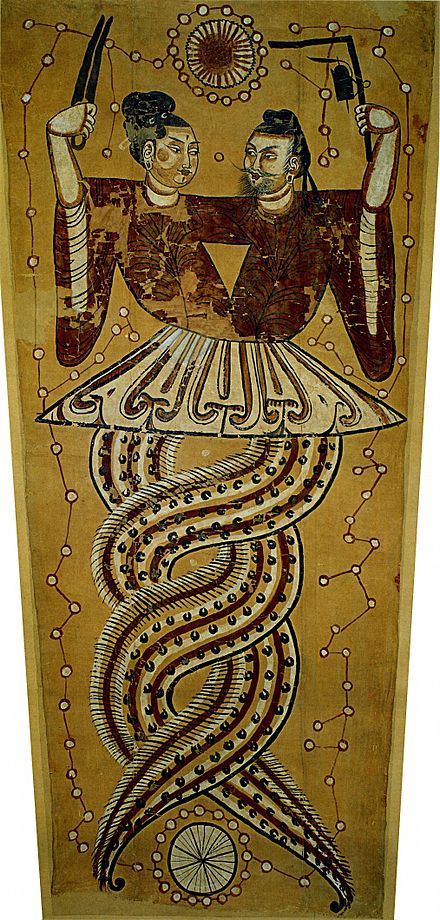

Definitely Zen Buddhist monks were one of the pioneers in pure tea drinking culture as it helped them with focus and meditation. It started earlier than Song in the Tang monasteries and there was a famous monk who could whisk tea so beautifully that for each bowl of tea he whisked, he could write a stanza of poem on the froths and together they formed a poem.

Full marks might be the gold standard for Asian moms, but this is like an A+ student who also got top achievement in the arts. Bragging rights for sure.

Later on, the Japanese buddhist monks who went to China to study Zen Buddhism arrived at Mount Tian Mu in Zhejiang and also tea. They brought back the black Jian Ware ceramic teabowl to Japan thinking that it came from the Tian Mu mountains in Zhejiang, and gave it the name Tenmoku. This type of tea bowl became so highly regarded and ceremonial that you required to take courses on it and become certified before you can serve people in this teabowl. But that is another way that the Japanese government and system protects its traditional craftsmanship and ensure continuous patronage and a healthy ecosystem of funding for its arts, cos in Chinese, even I can own one and serve you tea though I know next to nothing about preparing them.

Coffee, Tea and Art

I mentioned earlier the monk who could write poems on tea froths. You probably are thinking about the similarity of that and Latte Art that was in vogue a while back?

So this is similar except with tea, and done 1,000 years before.

I asked Kenny and he said there were two ways of doing it, either with clear water like this:

so now you ask, I thought the best froths were supposed to be white and thick like wax, so how does white show on white? Can it get any whiter? I’m sorry this sounds racist but I assure you this is just about tea art and froth.

So there is apparently another method that Kenny shared—it was using tea powder, and sometimes you mix with some water to form a paste-like ‘tea paint’ to be painted over the white froth.

Some said that the Green Matcha is more Japanese and the White one is more Chinese. But Kenny clarified that both types existed in the Song dynasty and they gave them very poetic names—Jade Froth for the white one, and Emerald/Kingfisher Froth for the green one. Yes, Jade were often associated with white nephrite jade for the ancient Chinese (though there were red, green and other coloured jade as well but white was deemed desirable for gentlemen). The Green Jadeite that we often associate with ‘traditional Chinese jade’ is actually relatively much modern, in the last 100-200 years or so, and it is not Chinese but Burmese in origin.

So… Here’s the part that is the whole point of my article..

I Can Teach You, But I’ll Have To Charge

So if you don’t already know, we’re running a Yaji event which historically would be a social gathering of literati friends who engage in a range of artforms and with knowledge exchanges and discussions. The inaugural edition, we’re basing it on the Song dynasty and the Autumn theme.

One of the highlight workshop is a Song dynasty reconstruction tea workshop by Kenny Leong, a private tea practitioner who mainly hosted corporate guests like banks and luxury brands (you can read more in his bio). So I’ve known Kenny for a while now, and I’m always rather wary of extremely commercialised practitioners of traditional craft because I feel that if most of the times, traditions were just a fancy costume party while money making is the real deal for them. So I was relieved to know that Kenny is not one of those unscrupulous jade sellers or fengshui masters in Chinatown (you know that type..), and like me, we have a full time job so that our passion can be as pure and not tainted by commercial interests.

As part of this workshop, you can also opt to get your own Song dynasty tea kit set as in the photo below (completed with grounded tea powder) and whisk in your own leisure time at home:

Because I themed it to be Autumn/Fall, I’ve also added some finer touches to the Song tea set to include a touch of season—A polished shell cut and engraved into the shape of a gingko leaf.

You probably would associate the gingko leaf with the Japanese culture more, but the gingko is actually native to China although the Chinese term we use today were based on Japanese and Korean words for it when Gingko was introduced to these two places from China.

There are still Gingko trees of 1500 years old in China, believed to be planted by Buddhist monks in their monasteries as it was believed to be a holy tree.

The most viral one has to be this 1,400 year old one in Zhongnan Mountain in a Buddhist temple. Like the article said, it is definitely a perfect celebration of Autumn:

In case you would like to celebrate Autumn in Song style with us, we have a whole afternoon of activities lined up for you on 24 September, Saturday at the Stamford Arts Centre.

Traditionally, the elegant gathering would’ve been by invitation only amongst a close group of friends who shared similar taste in the arts or worldview. We are adapting the idea of it into a more public affair to open up to those whom we might not know personally, but would like to be part of this interpretive experience on ancient culture and arts.

This is our invitation to you, and you can get your tickets HERE or click on the image to access the ticketing site:

We are selling early bird tickets now until 24 August, and it is definitely a very worthy deal to purchase your tickets now!

Hanfugirl: The story of the Chu waist came from a book by an ancient political-philosopher–Han Fei. As with many things in Chinese literature, a spade is never called a spade. The story talks about how the ruler of the Kingdom of Chu loved to see his court officials with tiny waists. So all of them start starving themselves to strive to have the tiniest waist possible, in order to gain his favour. Over time, they all became really frail and could barely stand up straight, let alone provide sound advice to him. Han Fei used this story to caution leaders against favouring policies or people based on his own private and personal preferences, as this would cause the entire political climate to slant towards currying flavouring instead of doing what’s best for the country.

Hanfugirl: The story of the Chu waist came from a book by an ancient political-philosopher–Han Fei. As with many things in Chinese literature, a spade is never called a spade. The story talks about how the ruler of the Kingdom of Chu loved to see his court officials with tiny waists. So all of them start starving themselves to strive to have the tiniest waist possible, in order to gain his favour. Over time, they all became really frail and could barely stand up straight, let alone provide sound advice to him. Han Fei used this story to caution leaders against favouring policies or people based on his own private and personal preferences, as this would cause the entire political climate to slant towards currying flavouring instead of doing what’s best for the country. While it was a story, the mention of the tiny waist is likely to be reflective of the existing aesthetics during the period, otherwise the reference would have been lost on the readers. During that period, the wooden clogs were already invented and worn by people like Confucius as well. I had a special request that Xishi wore clogs to dance because she was known for her clog dance. It was said that the king even built a hollow hallway just for her to dance her bell and clog dance. As such, the moves of the dancer would have to be adapted to work around the constraint of the clogs.

While it was a story, the mention of the tiny waist is likely to be reflective of the existing aesthetics during the period, otherwise the reference would have been lost on the readers. During that period, the wooden clogs were already invented and worn by people like Confucius as well. I had a special request that Xishi wore clogs to dance because she was known for her clog dance. It was said that the king even built a hollow hallway just for her to dance her bell and clog dance. As such, the moves of the dancer would have to be adapted to work around the constraint of the clogs.

Elizabeth:

Elizabeth:

Elizabeth:

Elizabeth: